The parallel lives of Flóris Rómer and Gusztáv Zsigmondy met both during the War of Independence of 1848-1849 and in the archaeological research of Aquincum.

Gabriella Fényes

Soldiers of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 and the research in Aquincum

“Friends! The first Honvéd [National Guard] battalion has been established, and I have joined up. You know well how much even the enemy acknowledged our makeshift artillery, which up to now has been made up chiefly of young students. […] Friends! It is not your calling simply to bear arms or to parade with rattling swords on the streets. Through developing your skills, you can provide a significantly greater service to our homeland and yourselves. […] If, in the three years, to which we commit, you want to learn useful things, to train yourselves in the science of mathematics and engineering, follow my example! If a man, who has led a carefree and comfortable life, after 18 years can leave behind the safety of academia for a position as a non-commissioned officer, to dedicate himself wholly to the service of country, why would you, young men without a fixed path in life, not seize the finest opportunity to do better than languish from boredom and indolence as wretched philisters. […] Those among you, who have love of country, courage, willingness and skill enough to serve our country in this important field, join your friend and former teacher and apply as soon as possible at the Engineers’ Office, Vízi barracks, First floor, on the right.”

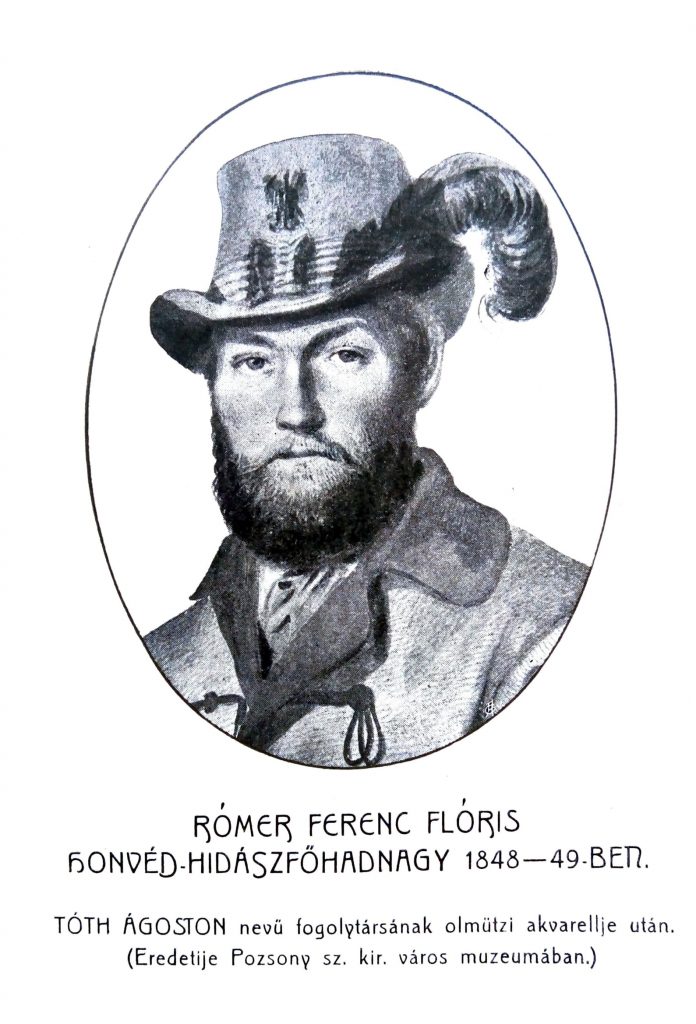

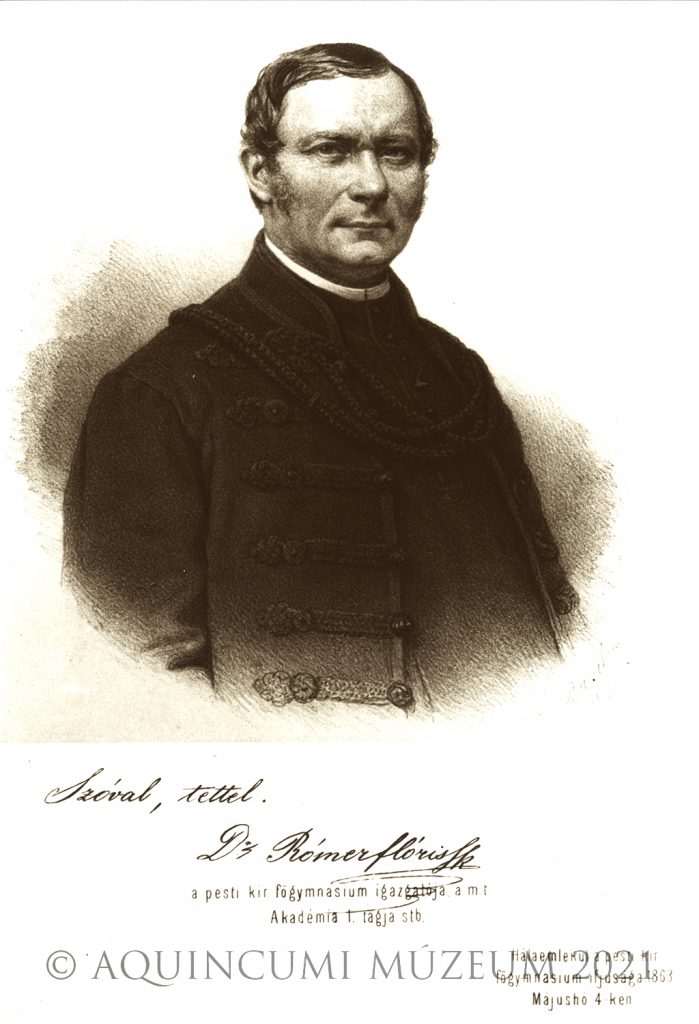

This appeal was written by Dr Római, a sergeant in the second company of engineers (formerly professor of natural history) on 13 November 1848 in Pozsony (modern-day Bratislava, Slovakia). It was in the autumn of that year that the first dedicated engineering battalions were set up for building earthworks and bridges and for facilitating the movement of the army. Lajos Kazinczy, youngest son of Ferenc Kazinczy (a noted Hungarian man of letters and language reformer), was commissioned as major to establish one of these units. General Artúr Görgei issued a call on 5 November to the craftsmen and youth of Pozsony to join the military engineers. On 17 November, Kazinczy, too, called on people to enlist as sappers. The 33-year-old Dr Ferenc (Flóris, to use his monastic name) Római (né Rómer), heeded the call of country. He left the monastery and a bright career at court (he was at the time professor at the academy in Pozsony and tutor to the Archduke Joseph, the son of Joseph, Palatine of Hungary), and joined up first as a volunteer, then, on 9 November, as a regular sapper. According to family lore, he recruited young men with spirited speeches delivered in the tavern at 1 Klarissza Street. His appeal, quoted above, made to his former students, was published on 16 November in the Pressburger Zeitung newspaper. For this, after the War of Independence had been crushed, a year after his enlistment, he was sentenced to “eight years of imprisonment in irons”.

First Lieutenant Ferenc (Rómer) Római (from E. Kumlik’s book on the Life and works of Ferenc Flóris Rómer)

The officers of the four military engineering companies established at Pozsony were commissioned by Lajos Kossuth, the head of the committee of national defence, in November. One of these officers was Gusztáv Zsigmondy, who became a lieutenant in the second company of engineers. His brothers also supported the cause of the revolution: Pál Zsigmondy headed the Hungarian Commercial Bank of Pest, which issued the so-called Kossuth banknotes of the war, while Vilmos Zsigmondy, who later attained fame through his artesian wells, defended the mines at Resica (now Reșița, Romania) as a mining engineer, where he also had guns cast for the Hungarian forces. The then-24-year-old Gusztáv had studied at the technical university of Vienna since 1845, and could put his experience as an engineering apprentice to good use in the new unit. On 18 May 1849 he was promoted to first lieutenant.

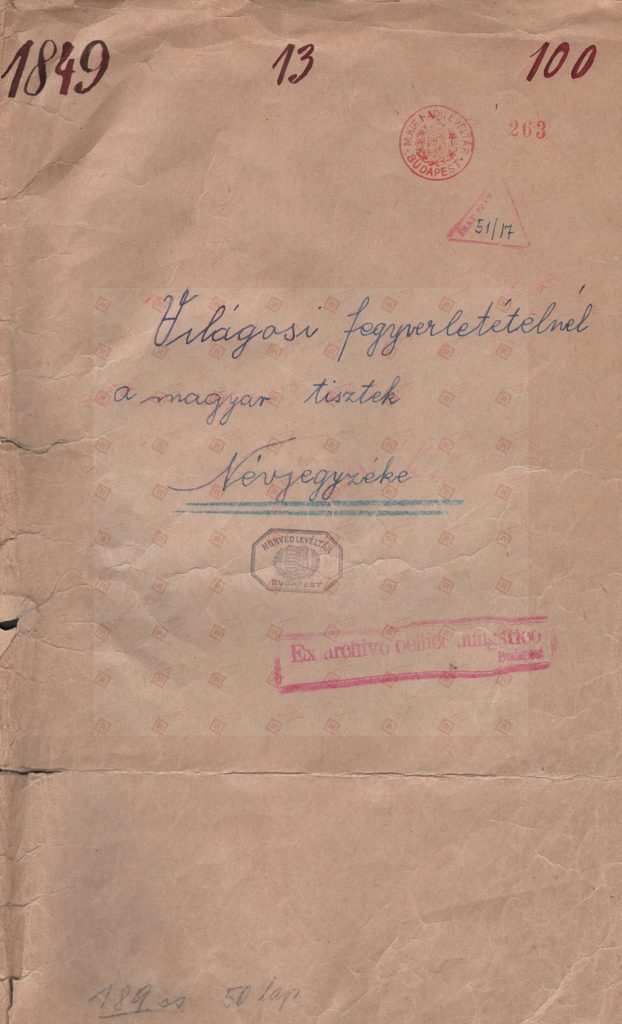

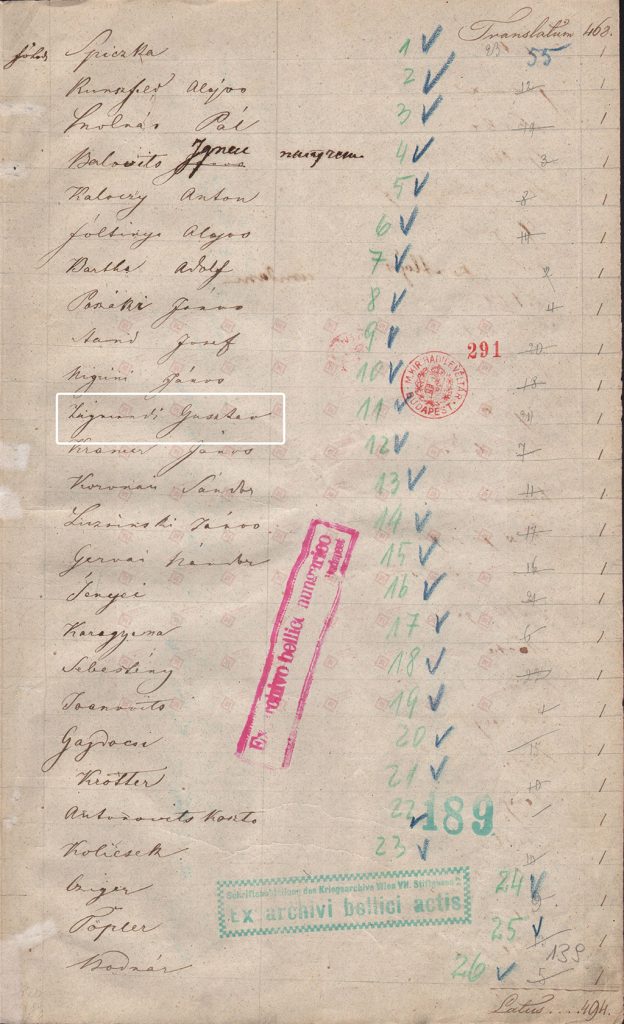

The stories reported by Rómer’s biographers of his military engineering days are the stuff of legends. Rómer rescued two engineering companies in Győr from the troops of the Austrian field marshal Windischgrätz; in the battle of Kápolna, he fired at the enemy using two ancient cannons from 1534; then, during the siege of Buda, he led his men up the walls on ladders at the Bécsi Gate. For his meritorious conduct, he was promoted to lieutenant in December and to first lieutenant on 30 March 1849. His unit, however, was routed in the battle of Debrecen on 2 August 1849. After the surrender at Világos (now Șiria, Romania) he fled north, but in Zólyom (now Zvolen, Slovakia) he was caught through the treachery of the postmaster of Nagyszalatna (Zvolenská Slatina, Slovakia) and taken to Pozsony, where he was sentenced to imprisonment. Gusztáv Zsigmondy, too, remained true to the cause until the end; his name was recorded in the register of officers made at the surrender at Világos. According to family tradition, he was forced into hiding after the War of Independence.

Gusztáv Zsigmondy’s name in the register of Hungarian officers drawn up following the surrender at Világos (Hungarian Ministry of Defence, Military History Institute and Museum – Military History Archive, Registry number: HL 1848-49 51/17)

20 years later…

“Heading past the brick factories above the Roman necropolis at the foot of Kiscell Hill, we arrived at the new site of the Victoria corporation. There, accompanied by the president of this brick manufacturing company, Lajos Poszner, Antal Kämeter, Dr Tatai and other shareholders, we respectfully received His Royal and Imperial Highness, presenting to the Crown Prince a map by royal engineer Gusztáv Zsigmondy, to inform him about the location and extent of the ancient capital of Lower Pannonia.”

Flóris Rómer published this report in 1869 in the Archaeológiai Értesítő [Archaeological Bulletin] on the Crown Prince Rudolf’s visit to Óbuda on 9 May. Rómer guided the young archduke (a child at the time), who was keen on the historical remains, around Óbuda with the help of his comrade in arms from 1848, Gusztáv Zsigmondy. During the visit, they first viewed a sarcophagus in Budaújlak, they then went to inspect the Roman graves and the gothic church remains (of Fehéregyháza) found at the Viktória brickworks (above the modern-day Bécsi Road – Vörösvári Road intersection). As time was short, they skipped the remains of the aqueduct. Lest the child catch a cold, they also avoided the ruins of the military baths, exhibited in a chilly cellar on Flórián Square, which greatly saddened Rómer. The main highlight of the visit was the inspection of the baths uncovered on Hajógyári [Shipyard] Island. The band of factory workers played the anthem, the “insatiably curious Crown Prince” asked for a stamped brick and two mosaic fragments as souvenir, the group then departed with the workers cheering loudly and waving their hats. As their final stop, they visited the Königsberg (King’s hill). In the cellars of the single-storey shacks there lay the walls of the military amphitheatre (of Nagyszombat Street) and in the arena there were vegetable gardens. Rómer highlighted the effect of the high-level visit on the growth of interest in the historical remains: after all “everyone wanted to see the little prince, who was intrigued by such antiquities, the importance of which they had not even suspected.”

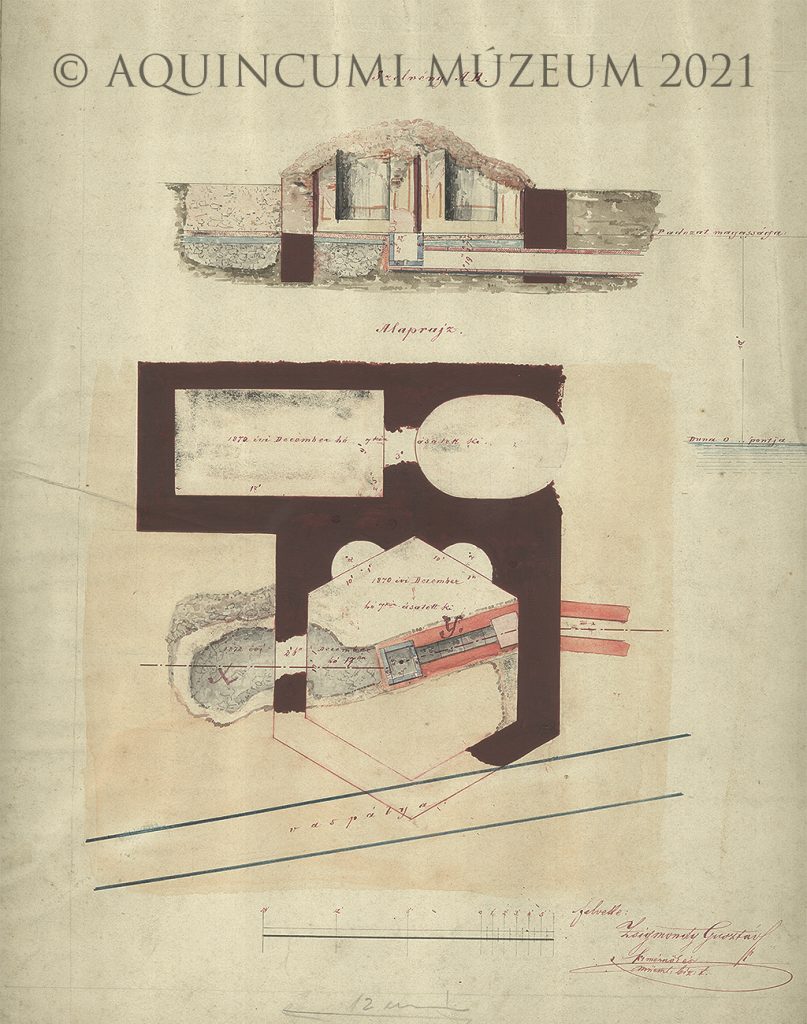

A drawing by Gusztáv Zsigmondy of the Roman ruins found on Hajógyári Island

Rómer moved to Pest in the autumn of 1861, where he worked at first as archivist of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, then between 1862 and 1868 as headmaster of the Catholic secondary school. In the meantime he became adjunct, then, from 1868, full professor of antiquities at the university of Pest. Not long after the archduke’s visit, he became keeper of the antiquities collection at the Hungarian National Museum; he was involved in reforming the museum since 1862. The indefatigable scholar was elected member of the Vienna-based central state commission for historical monuments in 1859 and the Archaeological Committee of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences in 1860. He became secretary of the latter in 1863. From that year, he also served as editor of the Archaeológiai Közlemények [Archaeological Publications] and from 1868 of the Archaeológiai Értesítő [Archaeological Bulletin] as well. In the meantime, he traversed the country, collecting historical remains and promoting the establishment of archaeological associations and municipal museums. He wrote a wealth of treatises on prehistoric, ancient and mediaeval archaeological remains. He had a passion for tracking down the Corvinus manuscripts of King Matthias and cataloguing bells and baptismal fonts. He put together the archaeological finds to be exhibited by Hungary at the International Exposition of 1867 in Paris. He attended conferences and visited museums in Hungary and abroad, introduced foreign scholars to the archaeological remains in Hungary. The 8th International Congress of Prehistoric Archaeology and Anthropology in 1876 was largely organised by him. He negotiated with the authorities regarding the protection of historical heritage and presented his research in a plain and accessible way to the general public. He knew that for the protection of historical-archaeological remains he would need to win public support.

Drawing of Flóris Rómer by Miklós Barabás

Rómer’s wide-ranging work also included cataloguing the Aquincum ruins and the collection of finds and stone artefacts. He was assisted in his endeavours by his comrade in arms from 1848, Gusztáv Zsigmondy, who was working at the time in Pest-Buda as a royal engineer. They were both dismayed by how the remains of the past were being destroyed by uneducated farmers, homeowners ‘quarrying’ the ruins for construction material, and the factory owners of Óbuda, which was becoming increasingly industrialised. “For years we have been standing idly by as the pillars of the aqueduct were disappearing, for years we have travelled on the Szentendrei road, built using Roman bricks, terra sigillata sherds, wall painting and splendid stucco ornaments. […] The traces of the town on the western side of the Roman aqueduct have all but vanished. The farmers took the walls apart, using them to build houses or to repair streets and the highway. We arrived with my friend Gusztáv Zsigmondy at the scene just as they were digging up the bottom course of the castrum’s western wall, to be carried off as fill for Kiscell street. What was once a part of Aquincum is not a plough field!” – railed Rómer in 1875. The municipality of Budapest did issue an order for the protection of archaeological remains (“Should one find antiquities while digging building foundations – e.g. stone coffins, stone carvings, vessels, metal objects, fossils, inscriptions – one must report the discovery to the municipal council at once and leave the discovered finds untouched until measures are taken by the council.”), however “no one has paid any attention to this”, wrote bitterly Gusztáv Zsigmondy.

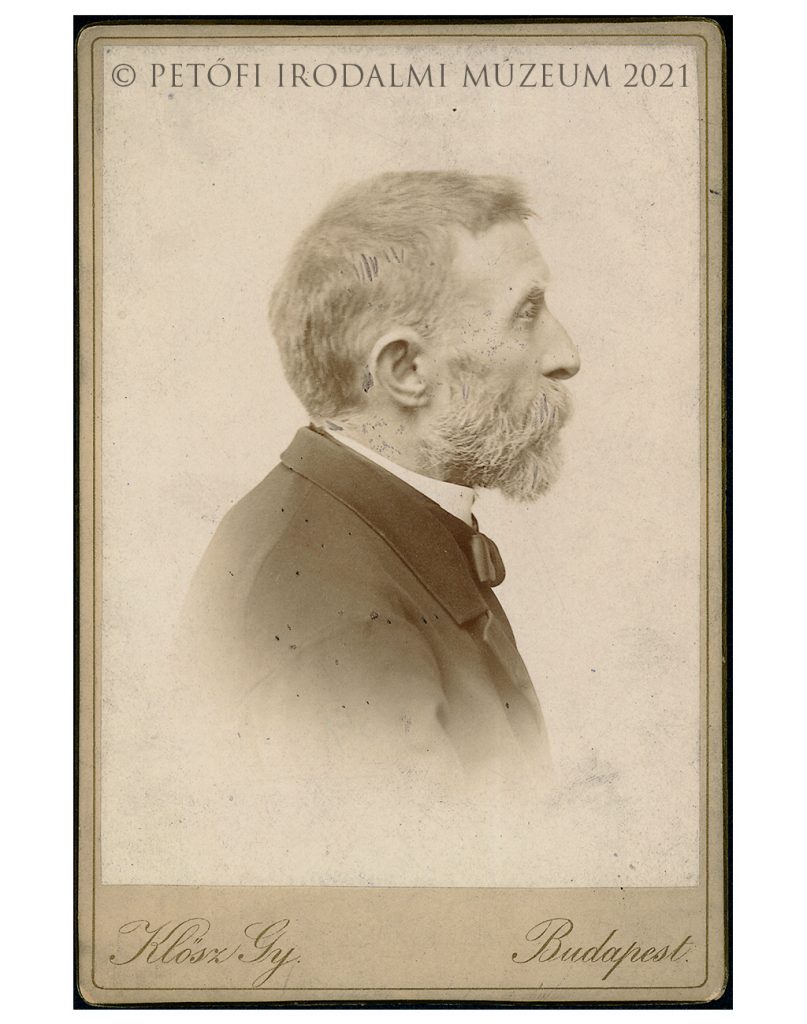

Photograph of Gusztáv Zsigmondy dedicated to the famous Hungarian author Mór Jókai (Petőfi Literary Museum)

In spite of all difficulties, their enthusiasm knew no bounds. Gusztáv Zsigmondy surveyed, among others, the remains on Hajógyári Island – identified as Roman baths at the time (they actually belonged to the governor’s palace) – the burials found at the Victoria brickworks, the graves discovered during the construction of the Óbuda distillery plant, and the extant ruins of the aqueduct arcade. In addition to cataloguing and drawing the remains, they marked on the cadastral map of Óbuda the precise location of the uncovered walls, roads, graves and major finds. The date on the maps, now held at the Hungarian Museum of Architecture and Monument Protection Documentation Centre, is 1875. Zsigmondy, however, continued the work even after 1877, when Rómer moved from Budapest to Nagyvárad (now Oradea, Romania). Rómer had a great role in raising the awareness of the authorities, the general public in Hungary, as well as foreign and domestic researchers regarding the finds from Aquincum. Thanks to their assiduous work – following the survey of the endangered ruins and the collection of finds discovered by chance during construction work – in 1880-1881 the systematic, scientific excavation of the remains of Aquincum could begin in Óbuda. This colossal undertaking of collecting, rescuing, and organising, was a war of independence of sorts for Rómer, a way to raise the standing of the nation. As he wrote: “Now we have a new opportunity to study scientifically a part of this wonderful settlement of the Romans [Aquincum] and present it to posterity. Through our labour we will show to the other nations of Europe that in this regard, too, we wish to belong among them.”

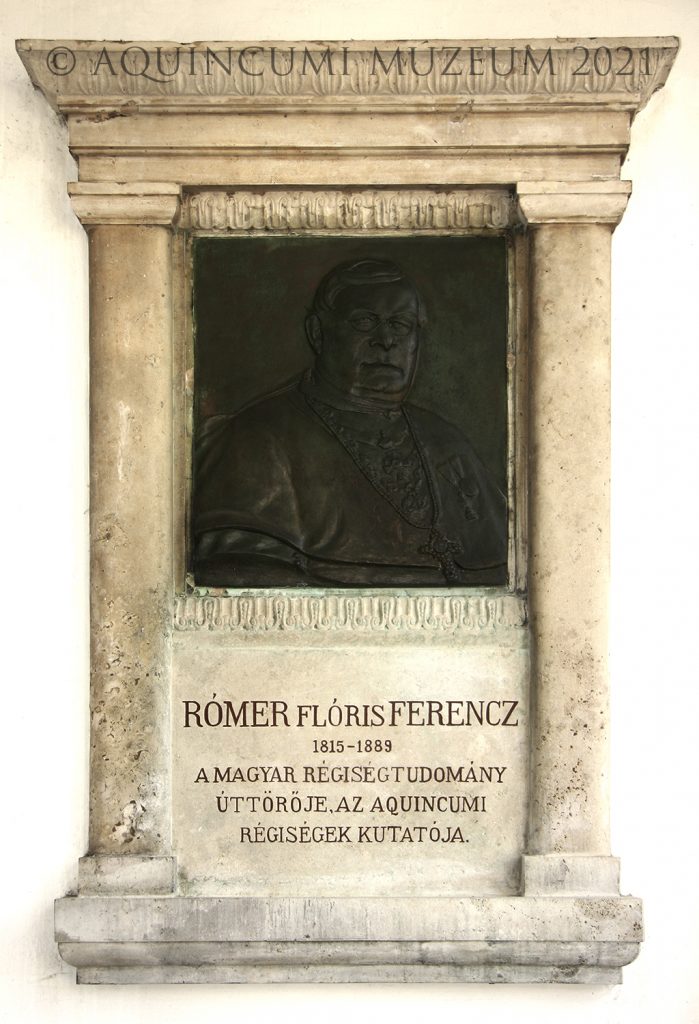

Flóris Rómer’s memorial plaque at the Aquincum Museum

The parallel lives of Flóris Rómer and Gusztáv Zsigmondy met both during the War of Independence of 1848-1849 and in the archaeological research of Aquincum. The following words from the funeral eulogy of Rómer by archaeologist József Hampel could apply to both Rómer and Zsigmondy: “He would not have been the passionate patriot that we knew him to be throughout his life, if the national movement had left him cold.”

For the images in the article, I would like to thank the Petőfi Literary Museum and the Military History Institute and Museum – Military History Archive. For the photographs held by the Aquincum Museum, I would like to thank my colleague, Krisztián Kolozsvári.

Bibliography:

Bona G., Az 1848/49-es szabadságharc tisztikara /Hadnagyok és főhadnagyok az 1848/49. évi szabadságharcban. https://www.arcanum.hu/hu/online-kiadvanyok/Bona-bona-tabornokok-torzstisztek-1/hadnagyok-es-fohadnagyok-az-184849-evi-szabadsagharcban-2/

Fraknói V., Rómer Flóris emlékezete. Századok 25, 1891, 177-199.

Hampel J. Emlékbeszéd Rómer F. Flóris rendes tagról. Emlékbeszédek az MTA elhunyt tagjai fölött. VI. 3. Budapest, 1891.

Hermann R., Rómer Flóris a szabadságharcban avagy, az életrajzírás nehézségei. Arrabona 51, 2013, 217-258.

Hermann R., A honvéd utászkar megszervezése 1848-ban. Hadtörténelmi Közlemények 132, 2019, 7-52.

Kumlik E., Rómer Ferenc Flóris élete és működése. Pozsony 1907.

Póczy K., Gondolatok Rómer Flóris emléktáblájának 100. évfordulóján az Aquincumi Múzeumban. Budapest Régiségei 27, 1991, 191-197.

Rómer F., Rudolf koronaherceg Ó-Budán. Archaeológiai Értesítő 1, 1868-1869, 237-240.

Rómer F., Ó-budai ásatások. Archaeológiai Értesítő 9, 1875, 111-113.

Szenthe M., Egy kivételes tehetségű evangélikus család nyomában. Evangélikus élet 2010/16/22.

Valter I., Szóval, tettel. Rómer Flóris Ferenc élete és munkássága (1815-1889). Budapest 2015.

Zsidi P., Rómer Flóris és Aquincum. In: Kerny T. – Mikó Á. szerk., Archaeologia és műtörténet. Tanulmányok Rómer Flóris munkásságáról születésének 200. évfordulóján. Budapest 2015, 17- 33.

Zsigmondy G., A régészeti leletek ügyének szabályozása a főváros területén. Archaeológiai Értesítő 7, 1887, 189.