No one likes it if the streets are dirty or that the roads are full of potholes, and certainly no one likes to be cheated at the market. It was no different in ancient Aquincum. In the Roman predecessor of Budapest there were dedicated officials to take care of this. They were called the aediles. In this instalment of our blog we will meet them and also come across once again the prominent town councillor M. Antonius Victorinus.

The story of the aediles goes back to the semi-mythical early period of Rome, as the office was born during the conflict between the plebeians and patricians. The original function of aediles in the city of Rome was, among others, to supervise the temples (aedes) of the plebs. After peace was restored and the position of aedile became an ‘accepted office of state’, their ‘job description’ came to cover ensuring the general welfare of the urban populace (e.g. grain supply, state of the streets, public games). In the imperial period, their importance declined, but in the Roman (and Latin) towns of the empire they continued to play a significant role.

The office was only open to freeborn and, naturally, wealthy men. In Rome, statesmen-to-be wishing to become aediles had to serve in a number of lower (civilian and military) positions beforehand, meanwhile in other towns, the aedileship could be the first office held. Both at Rome and in the Roman towns the aediles too had the right to wear the purple-bordered toga praetexta, the mark of high office.

Sacrifice offered at the Roman Festival of 2020 in Aquincum. The priest is also wearing a purple-bordered toga. Photo: Nóra Szilágyi

Vespasian, too, wore such a toga while aedile in the city of Rome. According to Suetonius (Suet. Vesp. 5), the future emperor did not put in too much effort in discharging his duties and the streets became covered in dirt. The emperor Caligula was not pleased and, as punishment, he ordered his soldiers to smear thoroughly the purple-bordered toga of the indolent official with the mud of the street. (Interestingly enough, this was not the last time in his career that Vespasian proved to be an excellent target. When he was governor of Africa, the rebellious people of Hadrumentum threw turnips at the future ruler (Suet. Vesp. 4).

Aediles in the towns of the empire supervised the local grain supply – in Petronius’s classic, the Satyricon, a guest at the dinner party thrown by Trimalchio (an all too perfect embodiment of Roman stereotypes about the nouveau riche) complains about the aediles being in league with the local bakers (Petr. Sat. 44). These officials looked after the streets, sewers and baths – among others these are the tasks we find mentioned in the Irni (a municipium in modern-day Spain) town charter issued in the final third of the 1st century C.E. (Lex Irnitana 19). Additionally, in e.g. the town of Urso, aediles were required to organise games (Lex Ursonensis 71).

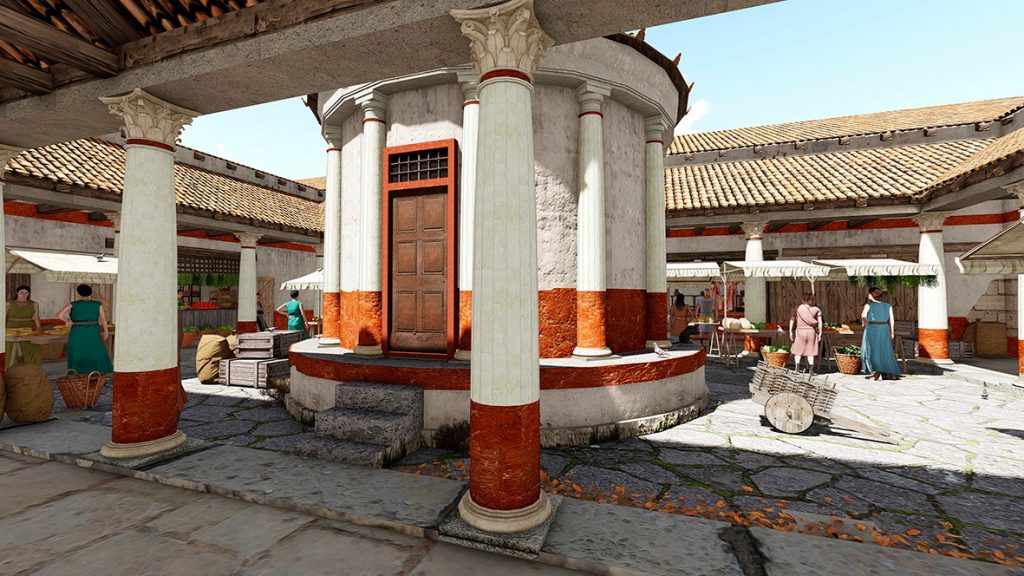

The Aquincum macellum in its prime. Artist’s reconstruction: Iceteam Design Ltd.

A key role of the aediles was the organisation of markets and fairs and the inspection of market halls (macella) as well as the weights and measures used there. In Apuleius’s satirical Golden Ass, we meet an aedile in precisely such a capacity; although maybe not of the best sort. When he finds out that his friend from out of town has been sold an overpriced fish, he goes to the market with his entourage, yells at the fishmonger and has his assistant jump on and crush the poor aquatic creature with his feet (Apul. Met. 1.24-5). A lose-lose situation at its finest.

In Aquincum (and in real life) conflicts were usually resolved using more practical and humane means. In the Civil Town’s market hall stood a circular building in the middle, the so-called tholos. This was presumably the office of the market-supervising aediles and their subordinates. During its excavation, archaeologists uncovered stone and lead weights, which represented the officially-sanctioned measurements. Through the use of certified weights, quarrels could be prevented.

Weights from the macellum in Aquincum. Photo: BHM Aquincum Museum, Photographic Archive

In the towns of the empire, two men were chosen every year for the position of aedile. As we have seen earlier, the importance of local elections during the imperial period declined over time. In Pompeii, however, even in the years leading up to the town’s destruction there appears to have been fierce competition for the aedileship. One candidate, a certain M. Cerrinius Vatia, even had to face a negative campaign! His opponents had messages painted on the walls of buildings which purportedly endorsed Vatia in the name of the ‘petty thieves’, ‘sleepy-heads’ and ‘late-night drinkers’.

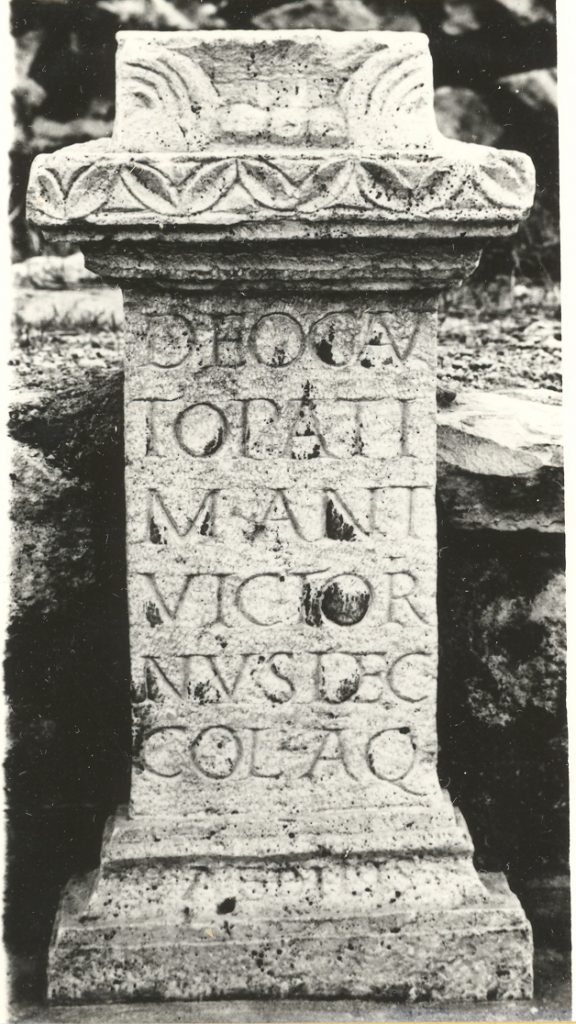

Altar from the Victorinus mithraeum. Photo: BHM Aquincum Museum, Photographic Archive

We have no account of such character assassination concerning Marcus Antonius Victorinus. It is certain, however, that he served as aedile in Aquincum. Based on the inscriptions found at the Victorinus mithraeum, which may be connected with him, he likely held this position in 223 C.E. Although his house is less than 100 metres from the Aquincum macellum, M. Antonius Victorinus could not have supervised this market building, as the hall would only be constructed in the mid-3rd century.

By then our friend in all likelihood also held the duumvirate. What that means will be the subject of our next entry.

Zoltán Quittner

Literature:

González, J. – Crawford, M.H.: The Lex Irnitana: A New Copy of the Flavian Municipal Law. Journal of Roman Studies 76 (1986) pp. 147-243.

Hornblower, S. – Spawforth, A. – Eidinow, E. (eds.): The Oxford Classical Dictionary. 4th edition. Oxford 2012.

Laurence, R. – Esmond Cleary, S. – Sears, G.: The City in the Roman West, c.250 BC–c. AD 250, Cambridge 2011.

Láng, O.: Stop.Shop (The world of workshops and shops in Roman Aquincum) Budapest, 2018. Available at the Aquincum Museum!

Mouritsen, H.: Local elites in Italy and the western provinces. In: Bruun, C. – Edmondson, J. (eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Roman Epigraphy, Oxford 2015, pp. 227-249.

Mráv, Zs. – Szabó, Á.: Új adatok Aquincum Severus-kori városi elitjéhez. M. Antonius Victorinus Aquincumban és Budaörsön. In: Kovács, P. – Fehér, B. (eds.) STUDIA EPIGRAPHICA PANNONICA (SEP)Vol. IV. TITE Könyvek 2, Budapest 2012. pp. 120-139.

Roselaar, S.T.: Local administration. In: Du Plessis, P.J. – Ando, C. – Tuori, K. (eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Roman Law and Society, Oxford 2016, pp. 124-136

Szabó, E.: A pannoniai városok igazgatása. Urbanizáció, önkormányzat és városi elit a Kr.u. 1-3. században a feliratok tükrében. Doctoral dissertation. University of Debrecen. Debrecen 2003.

Zsidi, P.: The Civilian Town at Aquincum. Aquincumi Pocket Guide 1. Budapest 2014. Available at the Aquincum Museum!

Click here to read the previous entries of the Aquincum Museum’s blog.