The Aquincum traffic jam blog, which brings you Óbuda’s hidden and not-so-hidden Roman remains, is back on the road. Next up: the amphitheatre of the Aquincum Civil Town!

So where are we now?

Last time we visited the northern wall of the Civil Town. This time, we’re not going very far. We continue our journey outside the ancient town walls, setting our sights on the Civil Town’s amphitheatre. We head north on the Szentendrei Road. After about 100 metres, at the zebra crossing, we cross the road and the HÉV suburban railway tracks. On the other side, we only need to take a few steps and there we are at the conserved ruins of the civilian amphitheatre.

But first the history!

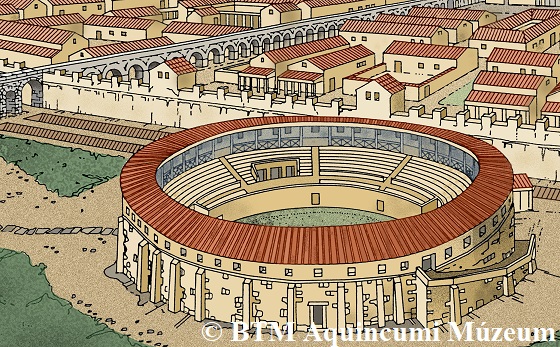

The amphitheatre of the Civil Town was likely built in stone during the reign of Antoninus Pius (138-161 CE). The venue was constructed to entertain the public with gladiatorial games, animal hunts, and, presumably, theatrical performances. According to estimates, it could accommodate up to four to six thousand spectators.

The action was often accompanied by organ music in the background. (Photograph by Nóra Szilágyi)

The seating arrangement at Rome was determined by law. The first row was reserved for senators. Behind them sat the knights (the Roman title of eques indicated a wealthy man, not necessarily a brave Sir Lancelot-type) and the other men, according to their social status. Ladies had to sit at the very back.

In the provinces we also find divisions of seats based on social status and group. As in other towns, in Aquincum, too, in all likelihood the town councillors (decuriones) and magistrates could have the best seats. Here, too, priests (like the Augustales of the imperial cult as for instance in Carnuntum [Bad Deutsch-Altenburg, Austria]) and certain respected professional groups (like that of the river boatmen in Nemausus [Nîmes, France]) may have had their own sections. We do know that the jailer of the legionary fortress had a reserved seat here. Inscribed on the benches of the civilian amphitheatre we also find the names of several seat owners without any special titles (or without their titles indicated!). These include Valerius Iulianus (who appears as a town councillor on another inscription), a certain Claudius Fabianus, and a matron by the name of Gaia Valeria Nonia. Seating was supposed to reflect the order in society.

The civilian amphitheatre following conservation

Order, however, could not be maintained all the time. Tacitus reports (Annals 14.17) that in 59 CE, gladiatorial games were held in Pompeii, which were also attended by spectators from nearby Nuceria. The two neighbouring communities opened with some banter, but soon they turned to stones and weapons. The Nucerians, playing an ‘away game’, were the less fortunate. News of the bloodbath also reached Rome, and the central authorities banned Pompeii from organising games for the next ten years. ‘Thanks’ to the eruption of Mount Vesuvius, a wall painting of the tragic event was preserved in the Campanian town.

‘Fans’ were not the only ones to cause tragedy. In 29 CE, at the Italian city of Fidenae, a great multitude of people flocked to a temporary, wooden amphitheatre. The structure, built most irresponsibly, could not hold the crowd and collapsed under the weight of the spectators. The number of casualties is uncertain. Our sources tell us about 20 000 dead (Suetonius, Tiberius 40) or 50 000 dead or wounded (Tacitus, Annals 4.63). Ancient historians and accurate statistics, however, usually do not go hand in hand. The organiser of the games was banished and basic requirements for the safe construction of amphitheatres were laid down.

From Aquincum and its two amphitheatres luckily we hear of no such tragedies.

What can we see today?

The 86.5 x 75.5 m civilian amphitheatre was a so-called ‘earth-amphitheatre’. The structure consisted of a rammed earth mound, surrounded by an external wall with buttresses and an internal podium wall 3 metres in height. Spectators would sit on the benches placed on the sloping mound.

Artist’s reconstruction of the amphitheatre with the Civil Town in the background (after Gyula Hajnóczi)

Spectators in this mid-sized amphitheatre were protected from the weather not by fabric awning (as in Italy), but presumably in part by a tiled roof (as indicated by the thousands of imbrex and tegula tile remains found here).

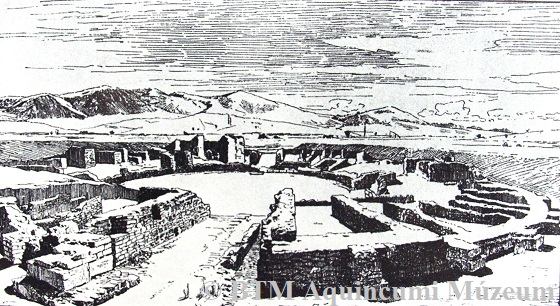

Although the structure was presumably still renovated in the third century, the abandonment of the Civil Town towards the end of the century also sealed the fate of the amphitheatre. “Above its ruins, over the centuries, a sizeable mound was formed, known by the local populace as the ‘Hill of Snails’” – wrote Bálint Kuzsinszky, first director of our museum in 1891. Some wall surfaces were reportedly still standing out from the ‘hill’ covered in countless snails even during the middle of the 19th century. It naturally garnered the attention of researchers, but the function of the walls remained uncertain for a long time.

The riddle was solved by Károly Torma who uncovered the amphitheatre between 1879 and 1881. This, and the excavation on the so-called ‘Papföld’ on the other side of the Szentendrei Road inaugurated the heroic age of Aquincum research and also led to the opening of the Aquincum Museum in 1894.

The civilian amphitheatre on a turn-of-the-century engraving

The civilian amphitheatre on a turn-of-the-century engraving

The conserved remains of the amphitheatre are now freely accessible to visitors. We can walk into the arena from the east through the so-called porta pompae ceremonial gate, where the procession would have entered prior to the start of the gladiatorial games. Victors would have left the arena via the porta triumphalis on the other side. In the podium wall, we can still see the animal cages (in addition to people, frequent ‘performers’ at the civilian amphitheatre included roe deer, wolves, wild boars, and presumably bears).

Soon we’ll continue our search for Roman remains as there are still plenty of other hidden and conspicuous monuments to discover in Óbuda; but more on those later.

Until then, take care!

Zoltán Quittner

18 November 2020

References:

Jones T. (2008) Seating and spectacle in the Graeco-Roman world [PhD thesis] McMaster University, Canada

Kuzsinszky B. (1891) ‘Az aquincumi amfiteátrum’ Budapest Régiségei 3: 81-139

Rawson E. (1987) ‘Discrimina ordinum: The Lex Julia Theatralis’ PBSR 55: 83-114

Torma, K. (1881) ’Az aquincumi amphitheatrum északi fele. Értekezések a történelemtudomány köréből 9.

Zsidi P. (2002) Aquincum polgárvárosa az Antoninusok és Severusok korában

Zsidi P. (2016) Archaeological Monuments from the Roman Period in Budapest.Walks around Roman Budapest (available at the Aquincum Museum)

Click here to read the previous entries of the Aquincum traffic jam blog.