The name is a sign, as the ancient saying goes. Indeed, a name can tell us a lot. Our surname for instance can indicate noble descent, the place where our ancestors lived, or the jobs that they had. But how was it like in Roman times? What does a Roman name tell us? Let’s meet one of ancient Aquincum’s residents, Marcus Antonius Victorinus.

The Roman name

First of all, let’s have a look at how the names of Roman citizens looked like. While at first Romans had one, later two names, by the start of the Imperial Period the use of the three names – the so-called tria nomina – became widespread.

The first part of the Roman name was the praenomen, e.g. Caius, Decimus, Marcus. Just as nowadays, there used to be some very popular first names in the Roman period. So much so that by the end of the Republic, only around 18 (!) such names remained in use. They were so common that they were consistently abbreviated on inscriptions, and later on essentially disappeared in non-official contexts.

The second element was the nomen gentilicium, e.g. Iulius, Antonius, Cornelius, which indicated to which gens (‘clan’) a person belonged. Here there were naturally more than 18 options.

The third component was the cognomen, e.g. Magnus, Caesar, Victorinus. While it often came from a personal (and at times less than flattering) nickname, the cognomen could be inherited. Thus it could be used for distinguishing between families within the same gens, or between brothers in a family, who shared the same praenomen and nomen. The cognomen could refer to appearance (e.g. Longus – tall), profession (e.g. Agricola – farmer), it could also be derived from the names of deities (e.g. Saturninus). The cognomen of the famous Roman statesman Marcus Tullius Cicero comes, for instance, from chick-peas (since, according to Plutarch, Cicero’s ancestor may have had a chick-pea-shaped wart on his nose. The Elder Pliny, however, writes that the name came from a chick-pea-growing forebear).

The names of Roman women were traditionally derived from their father’s nomen gentilicium, thus M. Tullius Cicero’s daughter got the name Tullia, and the daughter of C. Iulius Caesar was named Iulia. Freedmen took the praenomen and nomen of their former master. The name they had as a slave became their cognomen.

The Roman name of Russell Crowe

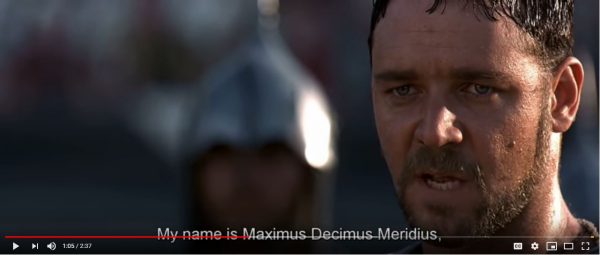

For two paragraphs let’s talk about the movie Gladiator. Although it’s set in Roman times and is immensely exciting, the film is rather far from historical accuracy. Going into this 19 years after the movie came out might not be very timely, nonetheless we must mention one detail.

(Source of image: YouTube)

“My name is Maximus Decimus Meridius.” Probably lots of people remember this key scene in the film, when Russell Crowe reveals his true identity to the Emperor Commodus, right in the middle of the Colosseum. It is without a doubt an impressive scene, but there’s a problem: his name! Maximus, after all, is a cognomen, Decimus a praenomen, and Meridius a nomen. Our hero’s name would therefore be (if he had actually existed, that is): Decimus Meridius Maximus.

And finally, Marcus Antonius Victorinus

M. Antonius Victorinus lived in the area of Aquincum around the late-2nd century and the first half of the 3rd century. His family probably came from the eastern parts of the Roman Empire. How do we know this? From his name!

While the nomen gentilicium Antonius can also appear frequently in the names of people from the Western provinces, the nomen Antonius combined with the praenomen Marcus, would primarily point to the Eastern territories and the activities of the famous triumvir Mark Antony.

Members of the so-called second triumvirate, Antony, Octavian and Lepidus divided the empire among themselves and Antony got control of the East. Just as manumitted slaves took the name of their former master, free provincials who had not possessed citizenship rights took the name of the person, whom they could thank for receiving their Roman citizenship. In this case, in the final years of the Roman Republic, in the East of the empire, this person was Mark Antony. Later on, the Emperors granted citizenship, and so on inscriptions in Aquincum we can often come across the nomen gentilicium Ulpius (Trajan), Aelius (Hadrian), or Aurelius (e.g. Caracalla).

While only terse inscriptions of M. Antonius Victorinus survive, from his name we can nevertheless surmise the possible origin of his ancestors. Of course the number of inscriptions mentioning him is closely tied to the fact that Victorinus was no ordinary citizen. Among his titles we find decurio, aedilis and duumvir!

What do these titles mean? Stay tuned for the next instalment of this blog.

Zoltán Quittner

Click here to read the previous entries of the Aquincum Museum’s blog.