Earlier we met an Aquincum resident by the name of M. Antonius Victorinus from the late-2nd century and the first half of the 3rd century. Inscriptions from for instance the Mithras sanctuary built next to his house in the Civil Town tell us that Victorinus wasn’t just a simple citizen. Among other things, he was one of Aquincum’s decurions. What this means is the subject of our latest entry.

In many ways towns with Latin or Roman rights represented idealised ‘mini-Romes’. Reflecting this were their public spaces and buildings (e.g. the fora, baths, amphitheatres) and their political systems as well. Republican Rome’s political life revolved around SPQR – Senatus PopulusQue Romanus, the senate and people of Rome (although power primarily lay in the hands of the former and by the Imperial period it was vested of course in the emperor). Similarly, in municipia and coloniae founded throughout the empire we find a local citizenry and a so-called ordo decurionum (in the western half of the empire. Given its ancient urban traditions, the situation is somewhat more complicated in the East, so we’ll be concentrating on local politics in the West).

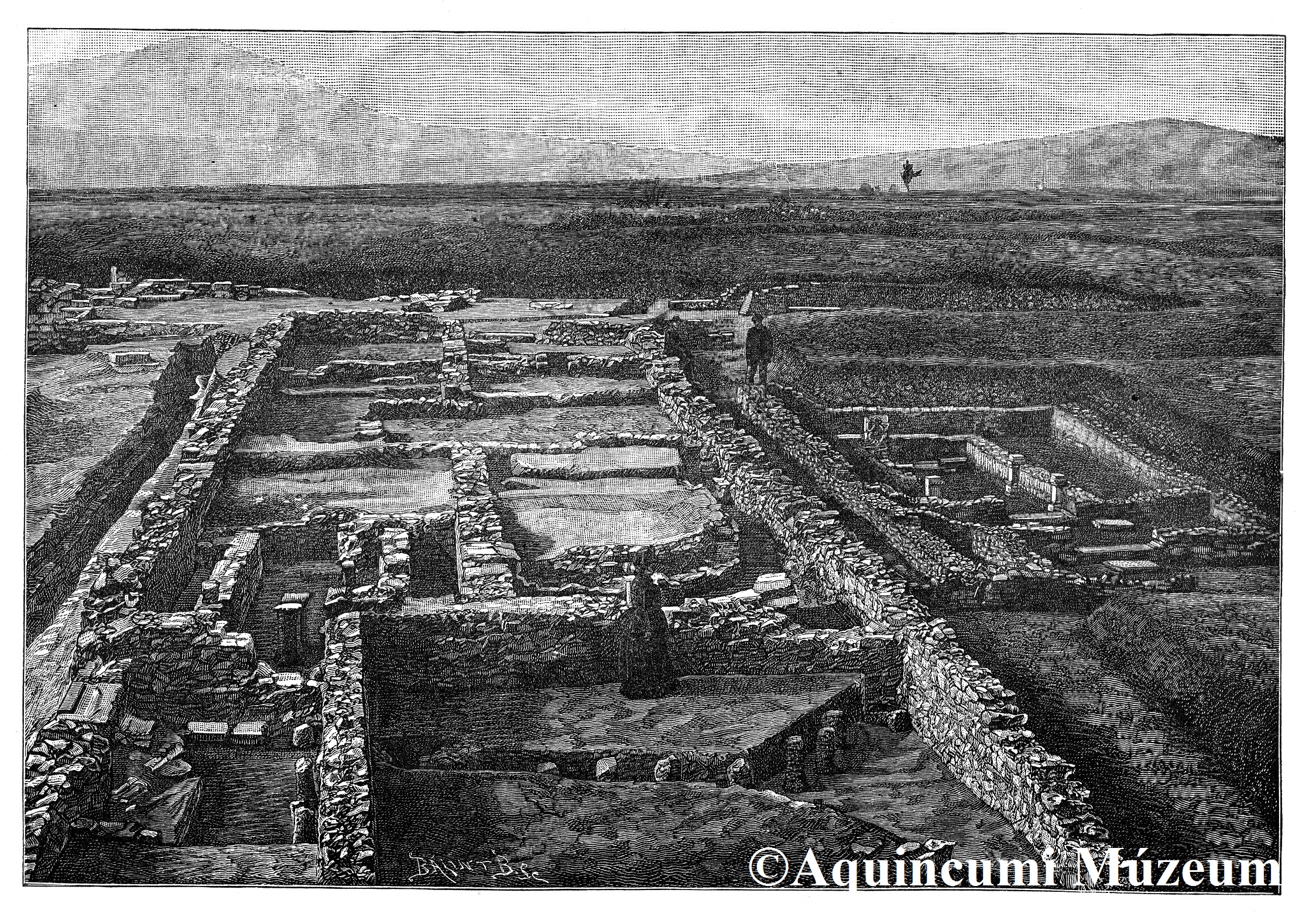

The Forum district of the Aquincum Civil Town. The eastern edge may have been the curia, the chamber of the local council.

Ordo decurionum

This was the town council, the local senate. They handled practically all local public business. They could decide on public buildings, developments and statues, they supervised the handling of public funds, sent requests to higher state bodies, oversaw the work of town executives etc. Pretty much like modern city councils. Of course, there were some major differences: e.g. decurions played an important role in the religious life of the community and they didn’t really depend on their ‘voters’.

Who could become a decurio?

Only those local citizens could become town councillors who met certain requirements. The suitable person reached the necessary age limit (usually 25), was freeborn (freed slaves were excluded), without a criminal record and – most importantly – was sufficiently wealthy! The required wealth depended on the size and prosperity of the community. In the small town of Irni (in modern-day Spain) in the late-1st century CE a net worth somewhat greater than 5 000 sesterces was all that was required, while at the same time in Italy those seeking to join might have needed 100 000 sesterces (just for reference, the annual pay of a legionary amounted to 900 sesterces in this period). We also find other criteria too, of course, e.g. at 1st-century-BCE Tarentum in South Italy a decurio was expected to own a house with at least 1500 roof tiles.

The house of M. A. Victorinus, with the Mithras sanctuary in the Archaeological Park (engraving from the golden age of Aquincum excavations). The number of roof tiles is uncertain, but the master of the house was undoubtedly well off.

And those who met the requirements?

Traditionally those could join the ordo decurionum, who had been elected by the people’s assembly to one of the important local functions (e.g. of aedile, ‘deputy mayor’; higher positions were reserved for those who had already completed a term in a lower office). Once his term was over, the ex-magistrate would eventually be enrolled in the ordo, where he could remain until the end of his life. This way voters could – if indirectly – influence the composition of the town council.

The importance of the assemblies, however, was on the wane. In Rome, under the Emperor Tiberius, they only retained a symbolic role. It appears, nonetheless, that in some cities rather competitive elections were still being held. In Pompeii we see political contests right until the destruction of the city in 79 CE.

Historians believe local elections lost their significance over time. It had been possible for some to become decurions without serving as a magistrate (this would have been necessary to fill the vacant places due to the death of councillors), but eventually the councils began to choose their own members and magistrates were chosen from existing decurions. We can see this in Ostia from the 1st century CE, but in Aquincum, too, we find decurions who held no magistracy, and also some who presumably became magistrates after having become members of the council.

In Pannonia we find few and tenuous references to elections. It is, however, interesting that in Troesmis (in Moesia, now Romania) the town charter dated to the late-2nd century, mentions elections and even electoral fraud! It appears that elections (at least in some places and perhaps with only symbolic significance) continued to take place.

Why become a decurio?

Decurions could decide on practically all local public business, collectively they ran the town. (Their number was proportionate to the town’s population. In the west historians take 100 to be the average.) Decurions enjoyed a privileged status, they had access to the best seats at the amphitheatre, and even the law was more lenient when it came to them. For instance, a decurio could not be tortured or sent to the mines, and could be executed only in a limited number of cases.

The Civil Town amphitheatre. Councillors in the front row.

The Civil Town amphitheatre. Councillors in the front row.

Councillors, however, received no salary. On the contrary, incoming magistrates and (from the second century) all new council members had to pay a significant entry fee of potentially several thousand sesterces (summa honoraria) and the wealthiest citizens were expected to lavish their towns with new buildings, gifts and games. It was the decurions’ job to oversee tax collection. If the tax paid by their town fell short of the expected amount, decurions had to make up for the difference from their own pockets.

The most successful local bigwigs could often move up and start a career with the imperial administration. Some even became senators. This, however, frequently meant severing the ties between the town and its richest citizens, leaving local affairs to the less well off. These were often unable to do so. In later sources we can read about town leaders bankrupted by their local duties and those finding loopholes to flee from the responsibilities (as well as the Emperor ordering that they be sent back to their towns).

How do we know all of this?

We can turn to ancient legal texts, chance remarks by Romans familiar with politics, various inscriptions by local magistrates. One of our chief sources, however, are the charters of the various towns. The public life of municipia and coloniae was defined by centrally-drafted laws. These cover countless local issues from town leadership to the manumission of slaves and the handling of court cases, to burial practices. The charters were engraved on bronze tablets and publicly displayed in the town centre. Unfortunately, the number of extant charters is limited, but there is still hope for new data. The fullest town charter to survive to date, the so-called lex Irnitana was found in 1981, the Troesmis fragment mentioned above came to light in 2002. And this year came the sensational news that in the Vienna Museum’s store rooms a young researcher discovered a small fragment (with a mere 41 characters) of the Vindobona town charter.

And last but not least: Marcus Antonius Victorinus!

Altars dedicated by M. Antonius Victorinus from the Mithraeum

Altars dedicated by M. Antonius Victorinus from the Mithraeum

Marcus Antonius Victorinus was a wealthy citizen of Aquincum who lived here in the late-2nd century and the first half of the 3rd century. His name appears on inscriptions in, among others, the Civil Town (where his house and the attached, so-called Victorinus mithraeum stood) and in Budaörs (on the southwest border of modern-day Budapest, where he owned an estate). He, too, was a member of the urban elite and the town council it comprised. Moreover, he was one of the most successful ones. In his career he attained the ranks of aedile, duumvir and pontifex. To find out what these mean, stay tuned for the next instalment of our blog.

Zoltán Quittner

Click here to read the previous entries of the Aquincum Museum’s blog.